The Power of Storytelling in Prison: From Healing to Re-integration

- Bhan Bidit Mut

- 30 janv.

- 7 min de lecture

Dernière mise à jour : 26 mars

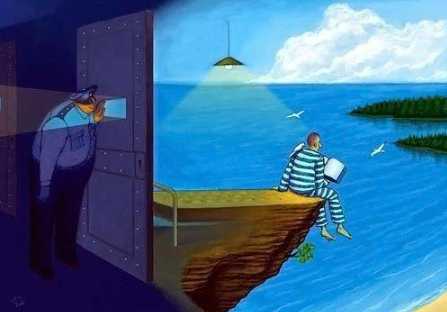

Storytelling, the art of conveying narratives through words, has always been a part of the human experience and goes beyond simple amusement[1]. People use it to connect with each other, discuss their past, and express their feelings[2]. This long-standing custom is especially important in prison settings, where alienation, trauma, and isolation are major problems[3]. Storytelling becomes a potent tool within these boundaries, allowing prisoners to explore themselves, build relationships, and get ready for re-integration into society[4]. According to this article, incarcerated people can benefit much from storytelling as a means of connection, healing, and re-integration into society[5].

For many prisoners, storytelling is an essential component of their therapy as it allows them to express their emotions and process trauma[6]. Sharing personal experiences enables individuals to face their history and express their emotions, both of which can have a major positive therapeutic impact[7]. For instance, inmates who participate in storytelling workshops frequently share how they came to significant insights about their decisions and their effects[8]. Research has shown that people who previously felt alone frequently find common ground and shared experiences, which results in emotional breakthroughs[9].

Another important component of storytelling inside prison walls is fostering empathy and understanding. As an example, inmates can develop relationships with one another and discover that they are not alone in their problems by sharing their stories[10]. By removing obstacles to judgment and promoting a sense of belonging, this method aids in the development of a supportive community among those who are incarcerated[11]. As they share their hopes, regrets, and fears, prisoners foster a culture of trust that can greatly lessen animosity in the prison setting[12].

Apart from providing therapeutic benefits, storytelling serves as a stimulant for individual development and self-discovery. More importantly, storytelling can force prisoners to consider their previous decisions, which results in important personal revelations[13]. Through this self-examination process, people frequently identify the behavioural patterns that led to their incarceration, which empowers them to make better options going forward[14].

Furthermore, storytelling enhances one’s ability to communicate[15]. Even in normal domains, people often find it difficult to put their ideas and feelings into words. But inmates can hone these abilities in a controlled setting through storytelling workshops[16], which enable them to speak with clarity and assurance. Their capacity to handle social circumstances after release from prison is improved by this development, which is beneficial not just for interactions inside the prison system but also for future contacts with the outside world[17].

The integration of storytelling into educational and therapeutic programs within prisons showcases its effectiveness[18]. Initiatives such as story circles and creative writing workshops have gained traction and demonstrated remarkable success in fostering personal growth and community building[19]. Collaboration with outside organizations and artists has enriched these programs, bringing diverse techniques and perspectives that inspire inmates to share their stories[20].

Research shows that participation in storytelling programs is associated with lower recidivism rates[21]. For instance, inmates who have taken part in storytelling programs often report feeling accomplished and hopeful about the future, which can inspire long-lasting behavioural changes[22].

Prisoners’ testimonials show how storytelling gave them a sense of direction and clarity[23], further confirming the behavioural effects of such programs. Storytelling is essential in helping incarcerated people develop a positive identity as they get ready for life after release[24]. By creating a personal narrative that highlights their development and life-changing experiences, inmates can start to envision a future that is different from the past[25].

This process of self-definition is important for building resilience and establishing a sense of agency[26]. On top of that, telling experiences to the public can help close the gap between prisoners and the community[27]. It promotes acceptance and tolerance by enabling people to share their stories, which are frequently complex and nuanced, dispelling myths and biases about those who have served time in prison[28]. These stories serve as a vehicle for society to interact with people who have done time in a more sympathetic manner[29].

Despite the numerous advantages, storytelling also poses drawbacks to prisoners. For example, while storytelling is viewed as one of the most reliable therapeutic techniques, sharing personal tales has usually had ethical implications, especially when it comes to consent and privacy concerns[30].

Thus, establishing a secure atmosphere that allows vulnerable voices to be heard without worrying about the consequences is crucial. Yet another hurdle may be opposition to narrative initiatives. As they have been judged in the past, prisoners may be hesitant to express themselves or doubt the advantages[31]. Facilitators who are aware of the subtleties of prison dynamics can foster the patience and trust necessary to overcome these obstacles.

Jefries, O., Haffman, D. M., Cathron, C., & Sommars, S. E. (2024). Storytelling: The essence of finding meaning in film and literature.

Green, M. C., & Appel, M. (2024). Narrative Transportation: How stories shape how we see ourselves and the world. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 70.

Pagan, M. (2024). “It never gets easier”. Understanding the adaptation and shattered realities of first-time prison entrants and their loved ones (Doctoral Dissertation, National University of Ireland Maynooth).

Brand, S. (2016). Lived experience of re-integration: A study of how former prisoners experienced reintegration in a local context (Doctoral Dissertation, Technological University Dublin, Sept 2016). DOI: 10.21427/D7JS6C.

Crier, N. D., Timler, K., Keating, P., Young, P., Price, E. R., & Brown, H. (2021, Nov 3). The Transformative Community: Gathering the untold stories of collaborative research and community re-integration for indigenous and non-indigenous people, post-incarceration and beyond (A). DOI: 10.142888/1.0406443.

Bove, A., & Tryon, R. (2018). The power of storytelling: The experiences of incarcerated women sharing their stories. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Criminal and Comparative Criminology, 62(15), 4814-4833. DOI: 10.1177/0306624X18785100.

Stephen, A. (2024). I am a person now I was always meant to be’: identity reconstruction and narrative reframing in therapeutic community persons. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 12(5), 527-547. DOI: 10.1177/1748895811432958.

Edmonds, M. (2024). Why we should stop thinking about violent offenders: storytelling and de-incarceration. Neulr, 16, 61.

Alexander, A. (2024). Narratives of Resilience: The power of creative expression and community support during familial incarceration. MS Thesis, University of South Florida.

Kelman, J., Gribble, R., Harvey, J., Palmer, L., & MacManus, D. (2022). How Does a History of Trauma Affect the Experience of Imprisonment for Individuals in Women’s Prisons: A Qualitative Exploration. Women & Criminal Justice, 34(3), 171–191. DOI: 10.1080/08974454.2022.2071376.

Little, R., & Warr, J. (2022). Abstraction, belonging, and comfort in the prison classroom. Incarceration, 3(3). DOI: 10.1177/26326663221142759.

Woodbridge, E., Vanhouche, A. S., & Lechkar, I. (2024). Islamic practices as powerful tools for coping with prison life: experiences of men in a Belgian prison. Justice, Opportunities, and Rehabilitation, 64(1), 25–42. DOI: 10.1080/10509674.2024.2433283.

Matranga, M. (2023). Perspectives of Self: Unreliable Narration, Women, and the Dynamics of Mental Illness. Open Access, Te Herenga Waka-Victoria University of Wellington. Thesis. DOI: 10.26686/wgtn.24223591.

Ronel, N., & Elisha, E. (2020, Feb 28). Positive Criminology: Theory, Research, and Practice. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Criminology. Retrieved Jan 28, 2025, from Oxford Research Encyclopedia.

Bordeos, M., Pecolados, M., Cardeño, R., Flores, J., & Bitangcor, S. (2023). The Impact of Cooperative Storytelling Strategy on the Learner’s Speaking Proficiency. Journal of Natural Language and Linguistics, 1(1), 22–30. DOI: 10.54536/jnll.v1i1.1987.

Suarez, A., Lee, D. Y., Rowe, C., Gomez, A. A., Murowchick, E., & Linn, P. L. (2014). Freedom Project: Nonviolent Communication and Mindfulness Training in Prison. Sage Open, 4(1). DOI: 10.1177/2158244013516154.

Morenoff, J. D., & Harding, D. J. (2014). Incarceration, prisoner reentry, and communities. Annual Review of Sociology, 40(1), 411-429.

Wendt Höjer, E. (2024). Captivating Communication: The Swedish Prison and Probation Service’s Storytelling and Creation of Legitimacy.

Liguori, A., Le Rossignol, K., Kraus, S., McEwen, L., & Wilson, M. (2022). Exploring the uses of arts-led community spaces to build resilience: Applied storytelling for successful co-creative work. Journal of Extreme Events, 9(01), 2250007.

Bunce, A. E. (2020). “What we’re saying makes sense so I’ve subscribed to it and I try to live by it.”: A qualitative exploration of prisoners’ motivation to participate in an innovative rehabilitation programme through the lens of self-determination theory (Doctoral Dissertation, University of Surrey).

Erny, B. (2013). A review of the effect of literacy education on the rehabilitation and recidivism rates of formerly incarcerated criminals (Doctoral Dissertation).

Cosimato, S., Faggini, M., & del Prete, M. (2021). The co-creation of value for pursuing a sustainable happiness: The analysis of an Italian prison community. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, 75, 100838. DOI: 10.1016/j.seps.2020.100838.

Storr, W. (2020). The science of storytelling: Why stories make us human and how to tell them better. Abrams.

Rodriguez Bellegarrigue, E. P. (2024). Re-authoring Violent Stories: The Impact of Trauma in Building Self-Efficacy in Incarcerated Men (Dissertation). Retrieved from https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-543903.

Empinado, G. A., Ledesma, A. R. C., Dano, R. B., Ligan, A. U., Figer, R. T., Guinitaran, A. M., & Pioquinto, P. V. (2023). Journey into transformation: Lived experiences of former inmates in therapeutic community modality program (TCMP).

Hamzah, I., & Kumalasari, F. H. (2018). Self-acceptance and significant others as a factor of the resilience of female prisoners with life sentences. Journal of Correctional Issues, 1(2), 90-99.

Pickering, B. J. (2014). “Picture Me Different”: Challenging Community Ideas about Women Released from Prison. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 48(3). Retrieved from https://cjc-rcc.ucalgary.ca/article/view/60985.

Urlińska-Berens, M., & Urlińska, M. M. (2021). Myths, truths and post-truths–adjustments to the portrait of a Prison Service officer. Resocjalizacja Polska, 21, 369-386.

Annison, H. (2022). The role of storylines in penal policy change. Punishment & Society, 24(3), 387-409. DOI: 10.1177/1462474521989533.

Lima, A. (2023). Understanding narrative inquiry through life story interviews with former prisoners. Irish Educational Studies, 42(4), 775–786. DOI: 10.1080/03323315.2023.2257673.

Corda, A. (2024). Reshaping Goals and Values in Times of Penal Transition: The Dynamics of Penal Change in the Collateral Consequences Reform Space. Law & Social Inquiry, 49(3), 1479-1509. DOI: 10.1017/lsi.2023.46.

Commentaires