Beyond words

- Lucrezia Ferrà

- 18 août

- 2 min de lecture

When Art tells stories

In a world increasingly hungry for stories, storytelling proves to be not only a means of entertainment, but also a powerful tool for reflection and growth, for transmitting positive values, sharing emotions and building identity. Commonly associated with verbal language – think of novels, oral stories, cinema – storytelling extends far beyond words.

In fact, there are many artistic languages that can become equally profound and effective vehicles of narration: among these, theatre and painting occupy a prominent place. Theatre: words that become body Theatre is, by definition, a multidimensional form of storytelling. The text is certainly a fundamental element, but not the only one. An actor on stage also and above all tells a story through their body, movement, tone of voice, set design, costumes and lighting. Every detail is part of the story and contributes to constructing meaning.

Think, for example, of physical theatre or mime, where words disappear completely, yet the narrative remains alive, intense and perfectly understandable. It is the actor's body that becomes language, conveying emotions, actions and conflicts through gestures, postures and rhythm. Even in the absence of dialogue, the audience understands, feels and experiences the story. Painting: frozen time that speaks, painting, apparently silent and immobile, is in fact capable of narrating in a surprisingly eloquent way.

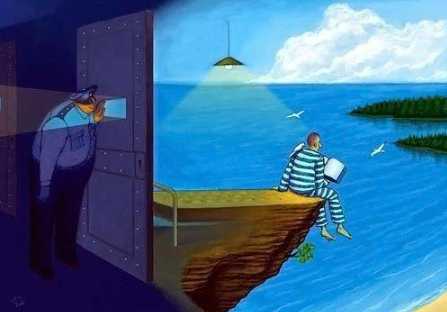

A painting can tell a story at a glance: just think of medieval or Renaissance painting cycles, where each scene is part of a narrative sequence. But even an abstract work, through its colours, shapes and compositions, can evoke inner stories, existential dramas or individual and collective dreams. Every visual choice is a fragment of a story: light, shadows, perspective, symbolic details. When looking at a painting, the observer is not a mere spectator, but a reader who reconstructs meanings through their own sensitivity and experience.

The story is not given, it is suggested, left unresolved, ready to be reborn a thousand times in the eyes of the beholder. What these art forms have in common is their ability to activate multiple senses simultaneously: sight, hearing, even smell and touch in the case of immersive performance experiences.

The story is thus not limited to being heard or read, but is experienced first-hand. This type of storytelling engages deep emotions, stimulates the imagination and breaks down linguistic and cultural barriers. Storytelling through art also means giving a voice to those who may not have access to words and overcoming language barriers.

Children, people with disabilities, communities with different languages: artistic storytelling can include, bring together and translate universal emotions into shared codes. In the prison context, low levels of literacy are often found and different languages coexist, making it essential to use different communication tools. Furthermore, the language of art allows access to more subtle and symbolic levels of meaning that often remain hidden in the folds of verbal language.

Opening our eyes to these narrative modes means enriching not only the way we communicate, but also the way we listen. Because, after all, every gesture, every colour, every silence can be a story just waiting to be discovered.

Lucrezia Ferrà’s article is a beautiful reminder that storytelling through art transcends language. Her description of theatre and painting as living forms of expression highlights how art can speak across cultures, abilities, and experiences. Through her reflection, she shows that every gesture, color, and silence holds the power to tell a story that can be felt deeply and universally.