Crowd Psychology and Inmates: A Study on Effective StorytellingMethods for Positive Outcomes in Prisons

- Ahmad Laith Mohamad

- 27 mars

- 5 min de lecture

Abstract

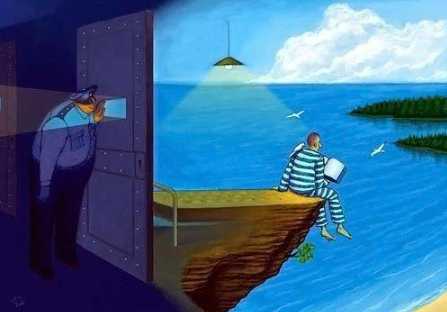

This paper explores crowd psychology and its impact on inmates, specifically focusing on how to prevent negative outcomes while sharing the story of a successful ex-prisoner. The aim of this study is to raise awareness among prison lecturers, helping them avoid significant mistakes.

We examine how telling the story of a successful ex-prisoner can inadvertently create a crowd mentality, where inmates idolize the individual in the story and attempt to emulate their path. We will demonstrate how to present these stories in a way that encourages inmates to adopt positive behaviors and view success as a goal, without elevating any individual as an idol.

For example, while figures like Nelson Mandela are often seen as symbols of resistance and freedom, we argue that the role of a prison lecturer is to share rehabilitative stories without promoting any specific ideology or individual as a model to follow.

Introduction

Inmates are particularly vulnerable and can be easily influenced by small acts or ideas that may lead them down a path of further despair. Therefore, when working with them, it is crucial to be cautious and sensitive.

When prison lecturers share specific stories, it is vital to ensure these narratives do not have a negative impact on the inmates. The primary goal of lecturers should be to strengthen the critical thinking of inmates, empowering them to become active, responsible citizens.

This paper focuses on the study of crowd psychology, particularly drawing from Gustave Le Bon's work, The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind. By applying key insights from Le Bon’s research, we aim to understand how prison lecturers can share stories without unintentionally manipulating inmates or fostering negative group dynamics.

Crowd Psychology and Inmates

Despite the emergence of modern psychological and sociological theories, Gustave Le Bon’s The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind can offer valuable insights into understanding and managing group behavior, especially within the context of prisons.

Le Bon explains that the term "crowd" takes on a new meaning during significant national events, when the individual’s conscious personality is overshadowed. In such circumstances, a collective spirit is formed, often transient, but with clear and crystallized characteristics. This collective entity exhibits a single mental unity, driving the behaviors of the group.

In the context of inmates, Le Bon’s concept of the crowd becomes highly relevant. When inmates are placed together, they may not form a psychological crowd by mere proximity, but the shared experience of imprisonment unites them under a common identity. This identity as "inmates" can foster a sense of solidarity, but it can also create a sense of collective thinking, which may lead to undesirable outcomes.

Instead of fostering individuality, this collective identity can weaken inmates' sense of self and their ability to critically evaluate their own behavior.

Le Bon’s insight into how crowds are formed by intense emotions or major events mirrors the situation in prisons. Just as revolutions or national events can provoke mass movements, incarceration can provoke strong emotional reactions—anger, hopelessness, or rebellion—that bond inmates together. When these emotions are amplified by the shared experience of imprisonment, they can create a "crowd mentality." Prison lecturers must be aware of this phenomenon and ensure that they do not reinforce such emotions through the stories they tell.

Le Bon also describes how the crowd influences the individual. He argues that the crowd suppresses individuality, leading people to act in ways they would not if isolated. Inmates, when grouped together, may lose sight of their individuality and instead conform to the collective mentality of the group. This could manifest in negative behaviors, such as reinforcing criminal identities, forming alliances based on shared grievances, or even following destructive leaders within the prison system.

For this reason, prison lecturers must be careful not to encourage inmates to identify solely with the collective "inmate" identity but instead empower them to recognize their individuality.

Le Bon further explains that crowds tend to be highly emotional and easily influenced, often by the most charismatic individuals within the group. This can be problematic in a prison setting, where inmates may idolize particular figures, whether they are fellow inmates or external individuals, such as former prisoners or political figures.

For example, telling the story of a figure like Nelson Mandela can be powerful, but it must be framed carefully. While Mandela’s story is one of resistance and empowerment, it could unintentionally create a sense of hero worship among inmates, leading them to idealize him rather than drawing inspiration from his actions to improve their own lives.

In a prison context, this crowd mentality could lead to inmates following one dominant figure’s ideology, neglecting their own personal development in the process. Le Bon describes how the crowd mentality suppresses critical thinking and promotes a sort of emotional contagion, where the emotions and actions of one individual are quickly adopted by others.

If an inmate is particularly influential, they could encourage others to follow their path, even if that path is not conducive to personal growth or rehabilitation. This dynamic could manifest in a prison environment where certain inmates manipulate others, creating a toxic atmosphere.

Le Bon also highlights the role of "provocateurs" within the crowd—individuals who stir emotions and lead others toward actions. In a prison, this could be any inmate or external figure who encourages others to conform to a specific ideology, belief, or way of life. These provocateurs can lead the group toward destructive behaviors or ideologies that undermine the rehabilitation process.

Therefore, lecturers must avoid presenting rehabilitative stories in a way that allows any individual, whether a historical figure or fellow inmate, to be elevated as an ideal to follow uncritically.

The influence of crowds, according to Le Bon, stems from emotional contagion, where the feelings and actions of one individual spread to the group. This makes it difficult for inmates to think critically about the stories they hear or the actions they take. Inmates, influenced by the emotions of the group, may adopt beliefs or actions without fully understanding or evaluating them.

Prison lecturers must work to counteract this by encouraging inmates to reflect critically on the stories shared, guiding them toward independent thinking rather than allowing them to be swept up in the emotions of the group.

Le Bon notes that crowds are easily agitated and driven by powerful emotions, often leading to irrational actions. This characteristic of crowds is particularly dangerous in the prison context, where emotions like anger and frustration can quickly escalate. Inmates, when caught up in a collective emotional state, may act impulsively or irrationally, which could harm their rehabilitation process.

To prevent this, prison lecturers must create an environment that fosters thoughtful reflection rather than emotional reaction.

Conclusion

When prison lecturers share the stories of public figures, such as Nelson Mandela, they must be mindful of their impact. The goal should not be to elevate any individual as a symbol to follow, but to inspire inmates to recognize their own potential for change.

Inmates should be encouraged to form their own beliefs and ideas, fostering self-awareness and critical thinking, rather than being manipulated into adopting specific ideologies. It is crucial for lecturers to avoid creating a sense of groupthink that could reinforce the crowd mentality and instead focus on empowering inmates as individuals capable of creating their own destinies.

This article gave me a lot to think about! I didn’t realize how easily stories could unintentionally create a crowd mentality among inmates. It’s really interesting how careful storytelling can help people reflect on their own choices without idolizing someone else.