Conference: Overcrowding in Belgian Prisons. Towards an AppropriatePenal System.

- Ana Ferrando

- 8 mai

- 2 min de lecture

The Perspective of an Educator

I arrived in Antwerp 18 years ago and soon learned that the Flemish cherish their "huisje, tuintje, boompje"—that little house with a garden where they can breathe in solitude.

Ironically, the same society that fiercely defends its private space tolerates prisons where three people share 9 m²—less room than the European law requires for a single dairy cow.

If private, personal space is fundamental for 11 million Belgians, why shouldn’t it be an essential condition in Belgian prisons?

Let’s step into prison life for a few minutes—but not without first quoting Dostoevsky in The House of the Dead (1862):"The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons."

As of April 15, 2025, Belgium has 20,346 people under some form of detention:12,877 incarcerated, with the rest serving alternative measures.

The maximum capacity of all Belgian prisons is 10,500. This means 1,500 people are crammed into cells never designed for such use.

And no, it’s not that Belgium has more crime; it’s that the system surveils more, punishes the same, and rehabilitates less.

But the real issue isn’t the numbers.

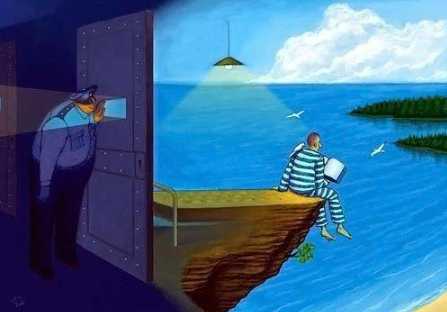

It’s what happens when you lock someone up for 22 hours a day in a cubicle where they eat, sleep, and live—with no distinction between smokers and non-smokers, violent offenders and the remorseful.

It’s that while the UN mandates 4 m² per inmate (Nelson Mandela Rules), here, they can’t even stretch their legs. It’s that the European Court of Human Rights has condemned Belgium for this for years, yet we keep paying fines instead of fixing cells.

Prison should be where mistakes turn into learning experiences. But how? One of my students, a recidivist thief, put it bluntly:"Professor, I don’t know how to do anything else. At four, my father took me stealing because I fit through the smallest windows."

Does anyone truly believe this boy will leave "rehabilitated" after years sleeping on the floor, with scarce access to psychologists or educators?

When we choose schools for our children, we evaluate the curriculum, facilities, and student-teacher ratios. Why, then, do we accept prisons—where education should prevent recidivism—lacking resources and staff?

Who would disagree that the education a person receives profoundly shapes their future?

The Council of Europe warns in its White Paper on Prison Overcrowding that when a prison reaches 90% capacity, it signals imminent overcrowding. This high-risk situation should push authorities to act immediately—yet Belgium’s system remains on the brink.

Coercive fines for overcrowding and inhumane conditions have piled up, with no quick fix in sight. But many are studying solutions. On April 26, the University of Antwerp and the Humanist League held a conference featuring judges, experts, and former inmates. I heard a lot of people wishing to make a change.

Slow and steady wins the race.

Every time we deny detainees their basic rights, we sabotage their reintegration.

In Belgian prisons, human rights are violated daily—in our name.

How long will we allow this?

This post raises such an important point. Overcrowded prisons don’t solve the problem they just highlight a system that needs deeper change. What really stands out to me is the call for a penal approach that focuses on rehabilitation rather than punishment. A fair system should not just contain people, but help them rebuild their lives.

Important insight, thank you so much for this