The Power of Non-Heroic Narratives

- Aurora DiTommaso

- il y a 6 jours

- 2 min de lecture

Justice and health are two fundamental rights in everyone’s life and they represent essential elements to build a democratic society. In prison, these rights intersect in a particularly delicate way: health is not simply the absence of illness but it includes psychological, relational, and emotional well-being as well as the opportunity to express oneself and make sense of one’s own experiences.

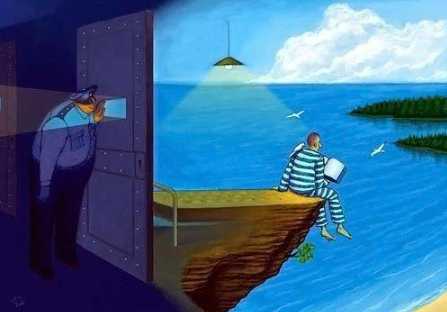

In sociology, prison is described as a “total institution” (Goffman, 1961) which means a setting characterised by an encompassing power over the individual that tends to compress the identity and reduce a person to a single role: that of the prisoner. In this context, non-heroic narratives take on a fundamental educational value: they provide a space where inmates can recognise themselves as a complex, imperfect and evolving human beings, restoring their voice, dignity and a sense of future.

In the prison context, the need for hope is profound and legitimate. In fact, the stories used in educational programs must make the possibility of change imaginable. Narratives built around heroic figures or exceptional transformations have the risk of creating a gap between the story and daily life in prison. When change is presented as an extraordinary, rapid and linear event, free of hesitation or contradictions, the story loses its educational value and becomes difficult to relate to. The risk is that such stories produce a sense of inadequacy, turning them into an abstract ideal.

The problem is not the happy ending, but the heroism on which it is built. Change has to be presented in small steps, in a gradual process and even in hesitation, fear, steps back, and mistakes. Being imperfect is not an obstacle to change, it is its condition. Stories work when they allow the listeners to see themselves, to say: “that could be me”. It is this realistic hope, rooted in shared human experience, that supports authentic and lasting paths of change.

This approach is deeply consistent with the principles of adult education and the concept of lifelong learning, which recognise the value of the person in their entirety and dignity. Equally important is that the stories are not solely about prisoners, but about mothers, fathers, workers, and citizens. In other words, narratives must reflect the multiple roles and interconnected experiences that make up a person’s life, helping to overcome the feeling of being defined only as an inmate and to restore a sense of full humanity. Such an approach also resonates with European values: it promotes inclusion by recognising the person beyond the crime; supports active citizenship by giving back voice and participation; and fosters social cohesion by building bridges rather than barriers.

In conclusion, non-heroic narratives offer inmates a space to explore their humanity, reflect on their experiences, and imagine a future beyond the prison walls. By valuing imperfection and complexity, these stories foster realistic hope and empower personal growth. At the same time, they encourage social inclusion, participation, and understanding, showing that education through storytelling can transform lives and strengthen communities.

Commentaires